Расскажите про цензуру в Саудовской Аравии. Я слышал vpn там часто синоним порнографии, к которой отношение очень плохое. Соответственно, она блочится. Есть дружинники, которые мониторят интернет на предмет “запрещенного”. Интернет дорогой, блочатся некоторые впны. Наверное по IP, не по сигнатурам. Запрещены voip сервисы, чтобы пользовались платным местным сервисом. Поэтому по whatsapp не позвонить. Местные были удивлены, когда узнали, что звонки через Tox работают. Вроде бы заблочены все .il домены, но я не уверен.

Я слышал историю одного иностранца, которого досмотрели. Как он говорит за использование vpn, но мне кажется за попытку открыть порно сайты + затем уже vpn. Поскольку впнами многие пользуются, особенно иностранцы. Многие популярные vpn сервисы заблокированы, но Express VPN почему-то работает, в том числе сайт. Вот то, что я знаю.

tango

September 12, 2023, 7:22am

2

I don’t have much personal experience, but BBS has two reading group posts that mention Saudi Arabia.

https://github.com/net4people/bbs/issues?q=label%3A%22Saudi+Arabia%22

opened 03:15PM - 25 Aug 20 UTC

reading group

Saudi Arabia

Opening Digital Borders Cautiously yet Decisively: Digital Filtering in Saudi Ar… abia

Fatemah Alharbi, Michalis Faloutsos, Nael Abu-Ghazaleh

https://censorbib.nymity.ch/#Alharbi2020a

https://www.usenix.org/conference/foci20/presentation/alharbi (video and slides)

This paper is the first systematic, longitudinal study of digital filtering in Saudi Arabia. The focus is on the filtering of web sites (the Alexa top 500 in 18 content categories) and social media / communications apps (18 apps such as iMessage, Line, and WeChat). The authors made three measurements, a year apart, between March 2018 and April 2020, from vantage points in four cities and three ISPs. The overall development since 2018 has been towards less filtering. There is a moderate decline in the blocking of web sites, and a marked decline in the filtering of mobile apps: of 18 apps assumed to be blocked in 2017, all but one (WeChat) were usable in 2020.

For each web site, they did a DNS lookup over UDP and TCP, a direct TCP connection to port 80, an HTTP request directly to the target web server, an HTTP request to a known-unblocked server but with the target domain name in the URL path, and a TLS connection directly to the target web server. From these tests they conclude that web site filtering is based on HTTP and TLS features, not DNS or IP address. Each domain name is either wholly blocked or wholly accessible, which means it is sometimes possible to, for example, read the articles of a blocked news site on an unblocked service like Twitter or Instagram. For mobile apps, they attempted to install each app on a phone in Saudi Arabia and a phone in the US, then use the app's text, audio, and video features. Over three years, apps that support voice and video calling have gone from being almost completely filtered to almost completely unfiltered. This latter phenomenon corresponds to a deliberate relaxation of policy towards communication-oriented apps that occurred in 2017. Some instances of filtering can be associated with specific political events. Examples include the blocking of ISIS-related web sites and certain foreign news sites.

Exceptionally for a study of this kind, the authors consulted with a government official and expert in local law, who stated that the study did not violate the law.

Thanks to the authors for reviewing a draft of this summary.

opened 07:56PM - 15 Aug 22 UTC

reading group

China

Russia

Iran

Saudi Arabia

Bangladesh

Weaponizing Middleboxes for TCP Reflected Amplification

Kevin Bock, Abdulrahman… Alaraj, Yair Fax, Kyle Hurley, Eric Wustrow, Dave Levin

https://censorbib.nymity.ch/#Bock2021b

https://geneva.cs.umd.edu/weaponizing

[Slides and video](https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity21/presentation/bock)

This paper shows how to do a certain kind of denial-of-service attack, a reflected amplification attack, using TCP and network middleboxes, like censorship middleboxes that inject block pages. Reflected amplification attacks traditionally rely on non-connection-oriented protocols like UDP: find a service that replies with more data than you send it, then send it some data, spoofing the source address of a victim host that will receive that reflected reply. In comparison, reflected amplification using TCP is usually thought to be infeasible, because an off-path attacker needs to guess the TCP server's initial sequence number in order to complete the TCP handshake, as well as prevent the victim from tearing down the nascent connection with a RST. But this paper makes a crucial observation: middleboxes often use TCP state machines that are intentionally simplistic. They may be designed to track flows even in the face of packet loss or asymmetric routing, for example, and for that reason omit certain required checks like strict sequence number matching. The laxness of these middleboxes can be exploited to cause them to send large volumes of TCP traffic, in situations where end hosts with full TCP implementation would not even consider a connection to exist. Apart from the novelty of using TCP, the attacks developed in this paper are noteworthy for the large amplification factors achieved. In some cases the amplification factor is infinite: because of some kind of self-sustaining feedback loop, the middlebox never stops sending traffic.

The authors use Quack (#2) measurements to identify network paths that are likely to contain injection middleboxes. They use Geneva (#23) to discover packet sequences that cause middleboxes on those paths to respond, starting from an initial seed of a PSH+ACK packet containing an HTTP GET request payload. Geneva finds five distinct packet sequences that can cause injection ([Section 3.3.1](https://www.usenix.org/system/files/sec21-bock.pdf#page=5)), as well as packet-level tweaks to optimize the amplification factor, like increasing the IP TTL and the TCP window scaling factor. They do an IPv4-wide scan using [ZMap](https://zmap.io/) to discover more middleboxes that are susceptible to the discovered packet sequences. These scans find over 5 million responders that have an amplification factor greater than 1, and over 50,000 that have a factor greater than 100. A substantial fraction of amplifying middleboxes can be attributed to national censorship firewalls. [Section 5.5](https://www.usenix.org/system/files/sec21-bock.pdf#page=11) is a targeted investigation into injection fingerprints from Bangladesh, Iran, China, Saudi Arabia, and Russia. The harms of censorship are known; this research shows that censorship infrastructure can cause harm even beyond its intended purpose: "Nation-state censors effectively turn every routable IP addresses within their country into a potential amplifier."

Thanks to the authors for reviewing a draft of this summary.

В 2018 году работал GoodbyeDPI, позволял зайти на thepiratebay, насколько помню.

Я ошибся, это было в ОАЭ, там с этим строже (можно привлечь внимание), хотя впн’ами люди тоже пользуются. Он не турист, а работает там. Точнее, его дочь с мужем. Порно не открывали, но муж работает на правительство, может в этом дело. Комп досмотрели, приложение VPN удалили. Также в стране заблокированы торренты.

UPD: Интересно, что Telegram зарегистрирован в ОАЭ…

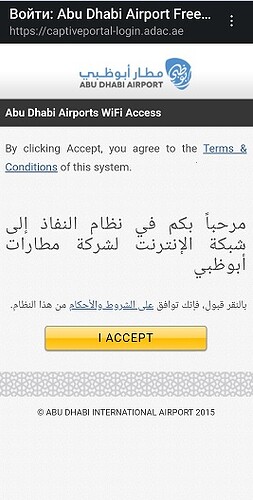

Подтверждаю, в ОАЭ (аэропорт Абу-Даби, AS5384), в Telegram и Signal заблокированы видеозвонки, через Riseup ограничения обходятся. Так же заблокирован сайт https://ntc.party/ .

был на днях