Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China’s Great Firewall

Margaret E. Roberts

This book examines Internet censorship in China using research and case studies. The central question addressed by the book is this: why do governments censor, when censorship is technically possible to circumvent? Roberts’s position is that, in China and elsewhere, the fact that censorship impedes access to information, but does not block it completely, is not a flaw but a feature. This “porous” censorship, in fact, serves the government’s policy goals better than would a firewall that was 100% effective at blocking. Censorship is best understood not as a ban, but as a tax on information that makes some things relatively more expensive to access—in terms of time, money, and inconvenience. The economic metaphors of cost and competition reoccur frequently, and help to explain some observed behaviors of censors that, at first, appear irrational.

Roberts identifies three modes of censorship: fear, friction, and flooding, devoting a chapter to each. Fear is what many people think of when they think of censorship: overt rules about what is permissible to access, and penalties for violations. (A primary contribution of the book is that fear, as a mechanism of censorship, has non-obvious disadvantages for the censor that may cause it to prefer the alternatives of friction and flooding.) Friction is putting up barriers that make information more difficult to access—even if it is technically possible to evade those barriers and there is no penalty for doing so. Flooding is when the censor tries to overwhelm online discussion by posting irrelevant and distracting information, creating competing alternatives to what it wants to obscure. These three modes are investigated through experiments on the Chinese Internet and Internet users in China.

A conventional understanding of censorship is that it is a question of deterrence: if the government catches you accessing something you’re not supposed to, you are thrown in jail or otherwise punished; fear of punishment is what keeps people from breaking the rules. Fear-based censorship, however, turns out to have unexpected costs for a censor, and, in China, is comparatively little used. Among the disadvantages of fear-based censorship is that it must be visible: the censor must state what the rules are, and people must know when they have broken them. This can perversely create more interest in the prohibited information, meanwhile making the government an obvious agent of repression. Roberts describes experiments that show people reacting more in anger or curiosity than in fear when they find they have been the victim of overt censorship. One experiment found matched pairs of social media posts (sourced from Weiboscope) from similar users with similar contents, where one user’s post was removed and the other’s was not. The authors of removed posts, instead of being discouraged by the removal, were more likely to continue posting on the same topic, and more likely to complain about censorship. Another experiment simulated the experience of reaching a block page when trying to read an online article. People who saw a block page were more likely to persist in trying to read about the article’s topic, and afterward were less likely to express support for Internet regulation. Despite its drawbacks, the Chinese government does employ fear-based censorship, but in a targeted way. High-profile people who have a wide reach—journalists, activists, entertainers—are more likely to be the target of intimidation and punishment. Ordinary people are, in comparison, at little risk of reprisal for creating or accessing restricted information—but the friction imposed by the Great Firewall means most of them rarely do so.

The book models Internet users as “rationally ignorant” consumers of information. There is simply too much information out there to consume it all; therefore people are selective about what they consume, and only spend time in accessing what they think will be worth the trouble. When the Great Firewall blocks a site, it increases the effective “cost” of accessing that site, cost being measured in all the annoyances that come with circumvention: acquiring a VPN, paying for it, reading documentation in a foreign language, etc. If the cost of access is sufficiently high, people will find something else to do with their time. Roberts frames the phenomenon in terms of “elasticity of demand” for information, in another economic analogy. If a blocked site is to be accessed, either the cost to access it must be low, or the demand to access it must be high; either circumvention is easy to use, or the information is so important it is worth the pain of using circumvention. The high general availability of information on the Internet creates an environment of elastic demand: even mild inconveniences become major obstacles when information is cheap and plentiful. But there are times—during sudden crises, for example—when demand becomes inelastic: the need for news overrides the friction of accessing it.

Roberts shares an experiment that shows how deletion of social media posts imposes friction on online discussion. Because fewer moderators work on weekends, posts made on Friday tend to persist longer before being deleted than posts made on other days—and discussion of sensitive events that occur on weekends is correspondingly more prolonged than those that occur on weekdays. Another experiment compares Twitter posts that are geo-tagged as being from China, where Twitter is blocked, and from Hong Kong, where Twitter was not blocked at the time of the experiment, in 2014. About 1.7% of Internet users in Hong Kong posted on Twitter each day, while only 0.2% of Internet users in China did so. The fact that there are posts from China shows that some people do use circumvention—but the far lower proportion of users in China, compared to Hong Kong, is attributable, at least in part, to the increased friction of accessing Twitter from China. In comparison with Sina Weibo, a Chinese service similar to Twitter, Chinese Twitter users were more likely to post about politics, and more likely to use English words. Case studies of blocked web sites (Google in June 2014, Wikipedia in May 2015, Instagram in September 2014) show that the blocks, even if circumventable in theory, were effective in decreasing access.

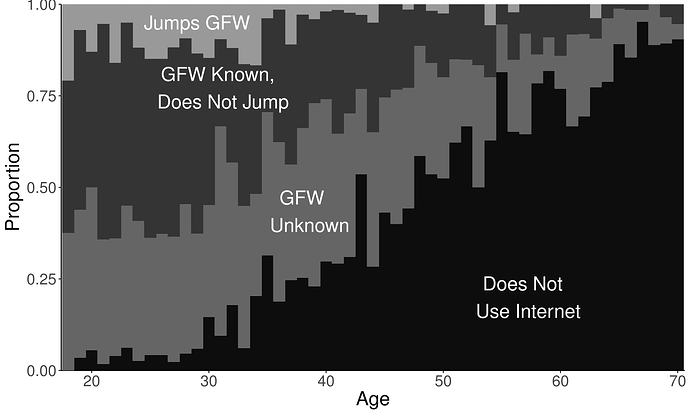

To me, the most striking part of the chapter on friction is the analysis of a survey of urban residents in China done in 2015. The main conclusion of the analysis is that not many people jump the wall, despite the low cost of doing so. The chart below, Figure 5.3 from the book, is sobering. Only 60% of urban respondents had ever used the Internet; of these, only 52% knew there is something called the Great Firewall and that there are ways to circumvent it. Only 5% of those surveyed had jumped the wall, ever. When those who had not were asked why not, their responses indicated they were negatively motivated not by fear, but rather by inconvenience, from not knowing how, or not having a reason to circumvent. Circumvention was correlated with age and education: those that had jumped the wall were more likely to be young, politically aware, and understand English.

Figure 5.3: Internet use, knowledge of the Great Firewall, and evasion of censorship by age.

The third mode of censorship discussed in the book is flooding, where governments coordinate efforts to derail discussion and distract people from unwanted topics. If friction diminishes access by increasing the cost of certain information, flooding accomplishes the same goal by decreasing the cost of alternatives. Flooding, as a mechanism of censorship, has the advantage that it does not bring attention to what the government wants to hide. It can be useful in a crisis situation, when elasticity of demand for information is low and friction alone is insufficient. The flooding apparatus in China is well developed, with news outlets receiving instructions from the Party on what stories to cover and how, and paid online commenters who make millions of posts per year in an effort to control and contain discussion. Roberts describes an experiment to uncover centrally coordinated news stories, by scraping the online edition of newspapers, measuring the textual similarity of stories, and correlating near matches with leaked propaganda directives. Coordinated news coverage happens particularly during sensitive times and on sensitive issues. A separate investigation into leaked email archives of a local propaganda department reveals some of the rationale and technique behind flooding. The goal is not to win debates, but rather to prevent debates from occurring. Flooding posts are not even always pro-government messages; they may be simply irrelevancies that do no more than drown out other voices.

A point made repeatedly is that the Great Firewall’s porous censorship has the effect of segmenting the population into groups and preventing them from working cooperatively. The most privileged segment of society, those who have the time, inclination, and knowledge to circumvent, may do so; everyone else lives with censorship, willingly or unwillingly. As Section 5.2.2 says, “the Firewall succeeds in creating a porous but effective barrier between a skeptical class and the public they would have to connect with to have a bigger political impact.” The fact that only relatively few people are capable of circumvention has the additional advantage, for the censor, of making that group easier to keep an eye on, and more susceptible to fear-based controls, like threats and harassment.

Thanks to Margaret Roberts for reviewing a draft of this summary, and for providing a copy of Figure 5.3.