I and my coauthors Cecylia Bocovich, Arlo Breault, Serene, and Xiaokang Wang are writing a paper about Snowflake. One big subsection of the paper is about blocking in Turkmenistan. Turkmenistan remains a challenge, but whatever we have been able to accomplish there has been aided by cooperation with locals, on this forum in particular. We are grateful for that.

Here is a draft:

snowflake.20230925.8d1cc535.pdf (862.6 KB)

The main request we have is to check if this is a fair way to describe network access and politics in Turkmenistan:

The blocking techniques just described are crude, surely resulting in significant overblocking—but they nevertheless offer greater challenges to circumvention than the more considered blocking of Russia and Iran. We highlight this to make the point that blocking resistance cannot be defined in absolute terms, but only in relation to a particular censor and its predilections. Censors differ not only in resources (time, money, equipment, personnel), but also in their tolerance for the social and economic harms of overblocking. Circumvention can only respond to and act within these constraints. The government of Turkmenistan has evidently chosen to prioritize political control over a functioning network, to an extreme degree.

Any other comments are welcome. Here’s the rest of the current draft section about Turkmenistan:

Blocking in Turkmenistan

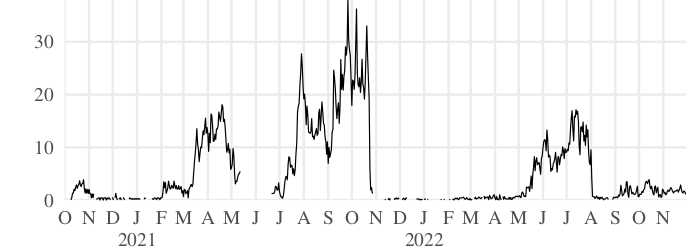

There have never been more than a few tens of Snowflake users in Turkmenistan. Even so, it has happened at least twice that the number of users dropped suddenly to zero, as you can see in Figure 10. We attributed the drops to multiple causes: filtering of the default broker front domain by DNS and TCP RST injection, and blocking of certain UDP port numbers commonly used by STUN.

Figure 10: Snowflake users in Turkmenistan. Though there have never been many Snowflake users in Turkmenistan, blocking events are evident on 2021-10-24 and 2022-08-03.Turkmenistan is a particularly challenging environment for circumvention. Though unsophisticated, the censorship there is more severe and indiscriminate than in other places we have seen. The fraction of the population that has access to the Internet is relatively small, which makes it hard to communicate with volunteer testers and lengthens testing cycles. We have been able to mitigate Snowflake blocking in Turkmenistan, but only partly, and after protracted effort.

The drop on 2021-10-24 was caused by blocking of the default broker front domain. We determined this by taking advantage of a feature of the Turkmenistan firewall, namely its bidirectionality. Nourin et al. [Nourin2023a §2] provide more details; we will state just the essential information here. Among the censorship techniques used in Turkmenistan are DNS response injection and TCP RST injection. DNS queries for filtered hostnames receive an injected response containing a false IP address; TLS handshakes with a filtered SNI receive an injected TCP RST packet that tears down the connection. Conveniently for analysis, it works in both directions: packets that enter the country are subject to injection just as those that exit it are. By sending probes into the country from outside, we found that the default broker front domain was blocked at both the DNS and TLS layers. It was some time—not until August 2022—before we got confirmation from testers that an alternative front domain worked to get around the block of the broker.

The increase in the number users from May to August 2022 visible in Figure 10 was caused by a partial unblocking of the broker front domain on 2023-05-03. We realized this only in retrospect, by looking at logs from Censored Planet [Raman2020c], a censorship measurement system that had continuous measurements of the domain at that time, in one autonomous system in Turkmenistan. There was a clear shift from RST responses to successful TLS connections on that date. DNS measurements are available only after that date, so they do not show a change, but they also showed no blocking. The unblocking evidently permitted some users to connect as before. But it must not have been nationwide, because as late as 2022-08-18, some users reported that RST injection was still in place for them (though DNS injection had ceased).

There was yet another layer to the blocking. Even if they could contact the broker (at the default or an alternative front domain), clients could not then establish a connection with a proxy. Further testing revealed blocking of the default STUN port, UDP 3478. A client that cannot communicate with a STUN server cannot find its own ICE candidate addresses (Section 2.2), which makes most WebRTC proxy connections fail. (The exceptions are proxies without NAT and ingress filtering. While there are some such proxies, censorship in Turkmenistan also outright blocks large swaths of the IP address space, including data center address ranges where those proxies tend to run.) As chance would have it, the NAT discovery feature we rely on for testing the NAT type of clients requires STUN servers to open a second, functionally equivalent listener on a different port [rfc5780 §6] (commonly port 3479). Changing to those alternative STUN port numbers let some users connect to Snowflake again. Specifically, STUN servers on port 3479 worked in AGTS, one of two major affected ISPs. The workaround did not work in Turkmentelecom, the other major ISP, where port 3479 was blocked. Though we do not have continuous measurements to be sure, we suspect that the STUN port blocking began on 2022-08-03 and precipitated the drop seen there in Figure 10.

The blocking techniques just described are crude, surely resulting in significant overblocking—but they nevertheless offer greater challenges to circumvention than the more considered blocking of Russia and Iran. We highlight this to make the point that blocking resistance cannot be defined in absolute terms, but only in relation to a particular censor and its predilections. Censors differ not only in resources (time, money, equipment, personnel), but also in their tolerance for the social and economic harms of overblocking. Circumvention can only respond to and act within these constraints. The government of Turkmenistan has evidently chosen to prioritize political control over a functioning network, to an extreme degree. To paraphrase one of our collaborators: “What they have in Turkmenistan can hardly be called an Internet.” In a network already heavily damaged by oppressive policy, the marginal harm caused by the clumsy blocking of this or that circumvention system is relatively small. This explains the sense in which a resource-poor censor can “afford” certain blocking actions that a richer, more capable censor cannot.